Download the Topic of Interest (PDF)

During the 1980s and 1990s timberland and agriculture opportunities were initially added to the asset class ‘menu’ for some institutional investors. During this time, private market asset classes were experiencing a tremendous boom following the 1978 amendments to the Employment Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) which encouraged greater portfolio diversification and allowed corporate pension funds to allocate to private equity. Furthermore, President Ronald Reagan’s Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 effectively lowered the capital gains tax rate, substantially increasing the attractiveness of private market investments that provided higher growth opportunities. Investment syndicates ―effectively the organizers of these projects―marketed these opportunities to investors for longer-term lockup. During the early 2000s, institutional investment in timberland and agriculture grew substantially as attractive investment returns drew capital to the sector. In the last decade, interest has notably ebbed and flowed as returns softened and opportunities in other ‘real asset’ segments competed for investor capital. Investors remain drawn to both timberland and agriculture due to their low or uncorrelated private market asset exposure that can complement a broader diversified portfolio.

Executive summary

In this Topic of Interest white paper, we will aim to inform readers of the investment thesis for timberland and agriculture, detailing the return drivers and characteristics unique to each asset class. Next, we cover historical performance and how these asset classes might fit within institutional portfolios and contribute to portfolio return objectives. Here we touch on the commonly acknowledged issues around interpreting the volatility of private market assets, due to data lag and appraisal-smoothing effects. Last, we conclude with a Verus outlook on both Timberland and Agriculture in the current market environment.

An investment thesis: Timberland & agriculture

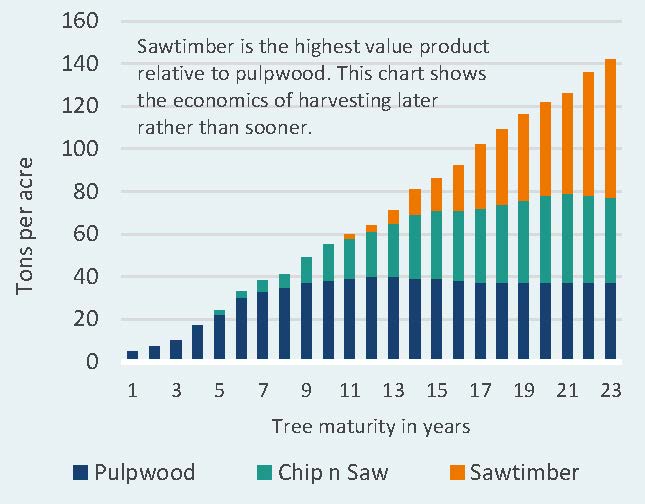

Timberland investing involves the acquisition of commercial tree plantations for eventual harvesting and monetary gain. This type of investment relies primarily on the biological growth of forests to drive returns over time, while also relying on the strength of the broader economy as economic trends help determine the tree stumpage¹ prices at which a timberland investor can ultimately sell their assets. Owners of these assets possess flexibility to harvest timber (or refrain from harvesting) in response to fluctuations in stumpage prices, which allows for some optionality and also reduces opportunity costs as trees continue to grow and rise in value if not harvested. Appreciation in land value is additive to return, and often correlates to inflation, but may also be bolstered by higher-and-better-use opportunities (i.e. selling the land to developers or land trusts). Additionally, investors may benefit from non-timber income, such as recreational leasing, mineral rights, mitigation banking and carbon-offset markets.

Global population growth and expanding needs for housing, paper, and wood, should bolster asset returns, all else equal. More specifically, the continued rise and wealth of the global middle class provides tailwinds to demand.

Investors may be drawn to timberland for the following reasons²:

- Moderate risk-adjusted returns: performance hit a peak in the 1990s and early 2000s, largely as paper companies sold off timber assets and home building activity took off. With the transition of timberland from paper companies complete, and as home building slowed following the global financial crisis, returns came down in the 2010s and are likely be muted in the future.

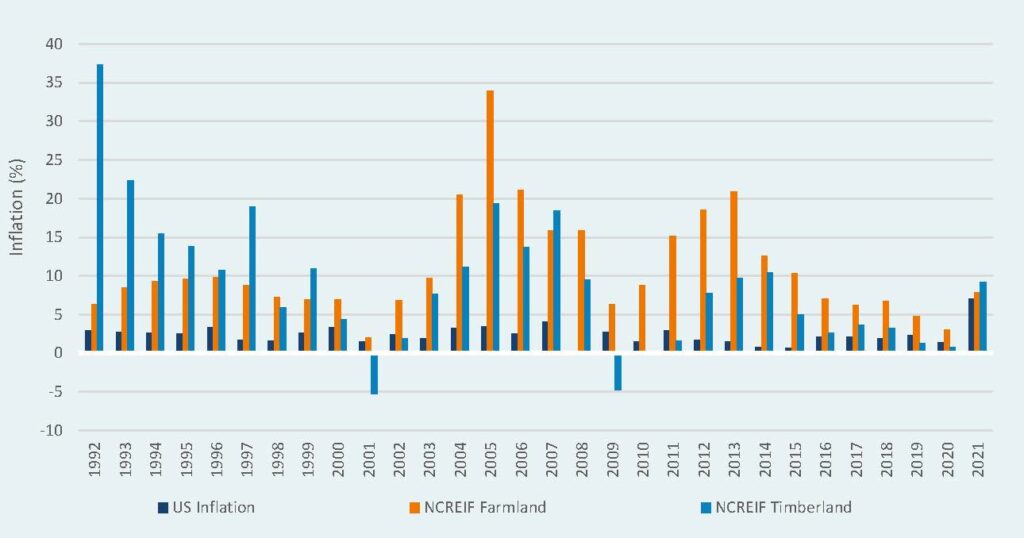

- Inflation hedging: similar to energy commodities and agriculture, timberland is a real asset and can arguably be somewhat beneficial as an inflation hedge. However, we believe this relationship to inflation is ambiguous. Timberland values are driven more by biological growth and sensitivity to home building trends and the housing market. The NCREIF Timberland Index (which we discuss later in this section) has shown a regression R2 value of 63.4% to inflation.

- Low correlation to other assets: This asset class, and the economic variables that influence its value through time, has been unique in behavior. Timberland may provide diversification value and lower the risk profile of a total portfolio by providing a lowly correlated return stream.

- “Soft” values: Timberland is, of course, an investment in forests, which may be a very attractive attribute for environmentally-conscious ESG investors. Certain timberland strategies focus specifically on sustainable forestry, offering investors the opportunity for competitive returns while also protecting forests and making a positive impact on the environment. Younger forests consume several times the amount of carbon dioxide that mature forecasts consume, and when trees are harvested for lumber projects the carbon is trapped inside. The planting of new trees restarts this process.

Disadvantages of timberland investing include its highly illiquid nature, and lack of ongoing income due to lumpy profit payouts and low commodity prices for trees.

The two primary types of trees are hardwood and softwood. Softwood trees make up much of the Pacific Northwest market (Spruce, Pines, Firs, Junipers) and Southeast market (Southern Pine). Hardwoods are generally grown in the Northeast/North Central Regions (Birch, Hickory, Maple, Oak, etc.). Trees grow approximately 5% per year in volume. This will depend on the specie of tree, the geographic location, age, and other factors. The age of tree at harvest time varies widely based on the type of tree and the global region, based on a 2010 study published in Biomass & Bioenergy³. In the United Sates, Loblolly Pine (30 years) and Red Pine (80 years) require a much longer lockup than, say, Loblolly Pine (15 years) and Rose Gum (15 years) grown in Brazil.

Below we illustrate the potential sources of total return for a timberland project, as well as a hypothetical yield curve for a Southern Pine crop.

Figure 1: Timberland sources of return

|  |

Timber Investment Management Organizations (TIMO) manage, invest, and operate timberland on behalf of investors. TIMOs can add value by improving crop yields, harvesting schedules and seeking higher and better use of the timberland (i.e. mitigation banking, selling to developers, etc.). Fund lockup terms will vary by strategy, but are often between 10 to 18 years in the United States. Unlike investments in agriculture farmland, timberland assets generally do not provide ongoing yearly income to investors, due to only periodic harvesting activity. This may make these assets less attractive to investors with an annual spending focus.

Investing in agriculture

Agriculture investment, also known as farmland, involves directly acquiring rural land to grow food for consumption or energy. This direct investment is typically handled by a specialist investment manager through a limited partnership structure. Specialist managers can provide proper diversification across crops and investment types, skill, and adequate scale, which would be otherwise unattainable if pursued directly. Agriculture investment can come in the form of lease arrangements where an investor collects ongoing revenue by leasing the underlying land to a farming operation, or through investment in both land and farming operations on that land. Underlying assets may include open land for cattle grazing, corn for ethanol, or soy, for example. Land operators may plant row crops (ex: cotton, wheat, rice) which can generally be switched out through the years for other types of annual crops. Permanent crops, on the other hand, are perennial crops which hold a longer-term growth period (ex: fruit orchards and nuts). The returns of agriculture are fueled by crop or livestock sales (or lease payments from farming operations), appreciation of the underlying land, and gains (or losses) from movement in commodity prices.

Investors may be drawn to agriculture for the following reasons:

- Ongoing yield & growth: Agriculture has offered investors a modest annual yield on investment, and performance that has historically been in line with public equity markets. As the global population continues to expand, investors can be fairly confident that the need for food will also expand. Additionally, a growing and increasingly wealthy middle class will likely result in diet upgrades to protein and more resource intensive foods, which creates further demand for agricultural land and production.

- Inflation hedging: agriculture produces a real asset (food or energy) which itself is an input into the rate of inflation. This makes agriculture a beneficial holding for investors who wish to protect their portfolio against inflation.

- Low correlation to other assets: This asset class, and the economic variables that influence its value through time, has been unique in behavior. Agriculture may provide diversification value and lower the risk profile of a total portfolio by providing a lowly (or non) correlated return stream.

- “Soft” values: Agriculture can be attractive for certain ESG investors. The social impacts of agriculture on local communities through job creation and provision of food could be compelling, depending on an investor’s mission. The global transition to green energy presents opportunities for biofuel production, as demand expands rapidly.

- Land price appreciation: Agricultural land is often in close proximity to urban centers. As urban sprawl occurs, the value of farmland may increase as developers seek new land for construction. Agriculture investors might think of this optionality as an additional benefit to the asset class. Furthermore, development activity may reduce supply of farmland, effectively lifting the value of other agriculture assets.

This provides a nice segue into the important differences between investing in agricultural land/operations and investing in commodities themselves (through the futures market). Other than the obvious liquidity differences, farmland investment differentiates itself by providing investors with the ability to participate in rising land values, an ongoing income stream, and some optionality from possible land development opportunities. The table below outlines these points4.

Figure 2: Agriculture investing versus commodity futures

Historical return & risk

Timberland as an asset class rose to prominence in the 1990s as international paper companies began selling off their timber holdings to institutions as a way to free up balance sheet capital. Timberland investments outperformed developed market equities for much of the 1990s and 2000s, as indicated in Figure 4, though we believe this was a one-time windfall due to the unique business activity occurring over that period. This performance weakened in the 2010s, falling closer to the performance of core fixed income. We believe returns are likely to remain moderate going forward, providing investors with a return between equities and fixed income. The asset class outpaced the rate of inflation in 77% of calendar years since 1992. Over the most recent ten-year period, ending December 31st, 2021, timberland delivered a 5.6% annualized return.

Agriculture investments fared well during the 2000s, weathered the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis with consecutive positive calendar year performance, and also performed well in the following years. In the mid-2010s, however, returns moderated and cropland prices flattened out. The asset class outpaced the rate of inflation in 100% of calendar years since 1992. Agriculture has returned 9.6% annualized over the most recent ten-year period, ending December 31st, 2021.

These figures are based on industry standard benchmarks for each asset class from the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries’ (NCREIF). Descriptions of each are provided at the end of this section.

Figure 3: Timberland & agriculture performance (10-year rolling)

Figure 4: Performance relative to inflation

Interpreting the risk of these asset classes is difficult, as is the case with private markets in general. The reported volatility of private assets likely drastically understates the true risk of those assets, due to appraisal-based pricing and lag effects. Investors do not know the true volatility of assets that are not traded daily on a market exchange (i.e. do not have an ongoing stated market price). To estimate the true value of private assets, a third-party appraiser is typically hired periodically to estimate the value of those assets. This creates two issues for the calculation of investment volatility (risk): First, the pricing of these assets is often too infrequent to calculate volatility using standard methods. Second, it is commonly acknowledged that those third-party appraisers tend to “anchor” the new appraised asset value to that asset’s most recently appraised value. This means that appraisals often understate the volatility of asset values.

Benchmarking timberland: The NCREIF timberland index5

The NCREIF Timberland Index is the most often used and cited benchmark for private timberland investment―the only such index that we are aware of. The NCREIF Timberland Index was founded in 1994, and collects performance data from institutional timberland investors. The index reports quarterly the performance of this composite of timberland investors, which can be thought of as being the best representation available of timberland performance as a broad asset class.

Benchmarking timberland: The NCREIF farmland index6

The NCREIF Farmland Index is a composite U.S. private market investment-only agricultural properties owned by tax-exempt institutional investors. The index tracks only income-producing properties, and includes permanent, row, and vegetable cropland. This index was founded in 1995 and reports performance data quarterly.7

The Verus view: Timberland & farmland market attractiveness

These asset classes are highly illiquid and in most situations are not suited to tactical investment opportunities. Both timberland and farmland involve long lockup periods, often greater than 10 years, and the decision to invest should take into account an investor’s strategic portfolio goals. With that said, below we have outlined our shorter-term views of the market environment for each asset class.

Timberland investing in the current environment

Timber has faced several headwinds since the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, as home building activity was slow to recover during these years, paper and pulp demand has fallen as paper usage has declined and as supply has come online from South America. Low interest rates and greater investor competition has pushed valuations up and made the market less attractive for new entrants. Following the headwinds faced during the U.S.-China trade war, the timber market hit another bump when COVID‐19 stalled exports to Asia and home building activity declined. Exports resumed in the Pacific Northwest and prices have recovered for Douglas Fir. Southern pine stumpage, on the other hand, saw little appreciation. Timber markets in North America appeared healthier in 2021, following several years of anemic transactions and low returns. Timber markets outside the U.S. face varying degrees of currency and political risk which in many cases has resulted in disappointing returns for investors.

Our shorter-term outlook on timber has been negative for several years due to the headwinds the asset class has faced. For most investors, mid‐high single‐digit expected returns for timberland in the U.S. may be too low for the illiquidity and risk assumed within the asset class. Fundraising has been slow to non‐existent for closed‐end timber funds for several years which has resulted in a slow transaction market. Though the NCREIF Timberland Index returned a respectable 9.2% in 2021, we believe there are more attractive opportunities elsewhere in real assets. With few exceptions, we believe the returns fail to justify the additional risk. However, we do see evergreen vehicles offered by certain timber managers to be a viable way to invest in timberland, though very large institutions may wish to fund a separate account.

Agriculture investing in the current environment

Agriculture investments fared well during the 2000s, weather the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis with positive calendar year performance, and also performed well in the following years. In the mid-2010s, however, returns moderated and cropland prices flattened out. The pandemic greatly impacted agriculture assets in 2020, driven by worker shortages, logistical problems, and a sharp slowdown in restaurant revenues which hit certain commodities very hard. Then, the year 2021 saw a meaningful jump in land values on the back of higher commodity prices. Supply disruptions from COVID-19, and more recently Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, have sent grain prices to multi‐decade highs, though we would expect those temporary price spikes to soon revert to more normal levels.

During the past year we have shifted from a negative view of agriculture to a more neutral position as the U.S. may be well situated to take market share and act as a stable supplier of agriculture commodities to the world. Income returns remain unattractive though the outlook for appreciation and some inflation protection has improved. Volatile commodity prices, however, do present risks to investors in this asset class. We would recommend diversifying across crop types and geography within the U.S. ― The War in Ukraine has revealed the extent to which Eastern Europe and Ukraine have been major suppliers of certain grains and their disruptions impact on global commodities. It has also highlighted the risk that comes from investing outside stable markets like the U.S. While Ukraine was not a preferred destination for U.S. institutional investors in agriculture, the returns available in emerging economies are not high enough to overcome the currency and economic/political risk.

As is the case with most assets, the multi-decade long fall in interest rates has generally led to higher prices and compressed returns. In other words, investors may reasonably expect lower returns from timberland and agriculture, going forward, relative to the performance of past decades.

Conclusion

In this Topic of Interest white paper, we outlined the investment thesis for timberland and agriculture and detailed the characteristics which make each unique. Next, we discussed historical performance, examining return and risk drivers from a holistic portfolio view. We believe there are more attractive opportunities than timberland elsewhere across the real assets spectrum. With few exceptions, we believe the returns fail to justify the additional risk. However, we do see evergreen vehicles offered by certain timber managers to be a viable way to invest in timberland. In agriculture, during the past year we have shifted from a negative view to a more neutral position as the U.S. may be well positioned to take market share and act as a stable supplier of agriculture commodities to the world. Income returns remain unattractive though the outlook for appreciation and some inflation protection has improved. Volatile commodity prices, however, do present risks to investors in this asset class. We would recommend diversifying across crop types and geography within the U.S. For additional information regarding our strategic and tactical views on timberland and agriculture, please reach out to your Verus consultant.

1 “Stumpage” is a term for the rights to cut down a standing tree, and the price paid to the landowner.

2 Fu, Chung-Hong (2014). Timberland Investments. Brookline, MA: Timberland Investment Resources, LLC

3 RISI Global Tree Farm Study and Fred Cubbage et al, “Global Timber Investments, Wood Costs, Regulation, and Risk” Biomass & Energy, 2010

4 (2013). Investing in Agriculture. TIAA-CREF Asset Management. Retried from www.tiaa-cref.org/assetmanagement

5 Index performance spans back to 1987, as this data was backfilled upon the founding of the index in 1994.

6 National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries. NCREIF Timberland Index. NCREIF.org. Retrieved May 20th, 2022, from https://www.ncreif.org/data-products/timberland/

7 National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries. NCREIF Farmland Property Index. NCREIF.org. Retrieved May 20th, 2022, from https://www.ncreif.org/data-products/farmland/