Download the Topic of Interest (PDF)

China’s ascension over the past twenty years to the second largest economy in the world has changed the global landscape in a variety of ways. As China’s economic size and market capitalization grows, many investors have reasonably been pondering how to treat their allocations to Chinese assets. In this Topic of Interest white paper, we will first briefly discuss the rise of China as an economic power and the development of Chinese asset markets. Second, we outline the average investor’s exposure to Chinese assets over time and how this exposure has naturally grown due to the changing market capitalization of Chinese assets, and also due to common benchmark providers significantly increasing the weight of China within those benchmarks. Third, we take a deeper look at the ‘China story’ that has led many institutions to allocate greater capital to this market, and identify the historical performance impact of Chinese assets on portfolios. Last, we offer some potential opportunities and threats around Chinese investment that should help provide context to investors in their decisions around this market.

The rise of China

A rich and varied history exists behind China and its rapid rise during the 20th and 21st centuries. Because the modern-day history of China’s economic and market development is not the core focus of this white paper, we have condensed key events into the table below, beginning in the year 1978 which arguably set the stage for China’s rise as a global superpower.

| Year | Economy & Regulation | Public Markets |

|---|---|---|

| 1978 | 1978 marked the end of the Cultural Revolution, and the beginning of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s significant economic reforms1, which involved a restructuring of Chinese society, ranging from privatization of farmland, granting of private citizens the ability to possess ownership of businesses, encouragement of foreign investment, and removal of certain government price controls. Deng Xiaoping outlined special economic zones, which would act as areas with reduced government bureaucracy, aimed at allowing foreign businesses to establish a footprint for trade. Reforms allowed China to begin ridding itself of inefficiencies that are common in centrally-planned communist systems, and resulted in: vastly improved agricultural output to avoid food shortages and famines that had been common, flexibility of goods and services pricing which led to efficiency gains in commercial transactions, and an influx in foreign business dollars to fuel growth. | The Chinese stock market was closed in 1950 during the communist revolution and remained closed during this time. |

| 1980s | During this decade these initiatives broadened. Business controls and restrictions were further lifted, while moving towards a more localized approach―delegating government decisions to local authorities which were often in better touch with community needs. Local governments also began liquidating certain institutions, leading to a wave of privatization and the first publicly traded Chinese bank and insurance company. | The Chinese stock market was closed in 1950 during the communist revolution and remained closed during this time. |

| 1990s | During the 1990s even more aggressive reforms were pushed through, and most state-owned enterprises were sold for private control. Deng Xiaoping passed away in 1997, though the campaign for reform continued through his personally-selected successors. However, concerns within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were growing about the possibility of private enterprises becoming too powerful on the national stage. China experienced strong economic growth during these years under Premier Zhu Rongji, and fared well during the Asian Financial Crisis. In 1996 China gains acceptance into the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Britain returned Hong Kong to China in 1997, after 99 years of British control. | The Shanghai Stock Exchange reopened in 1990, though stock prices were set by the CCP2. The Shenzhen Stock Exchange was also founded this year. However, stock ownership limited the holder to a dividend, rather than legal ownership. Market liquidity, structure, and transparency were weak, with stocks trading at different prices in different regions. In 1992, the ‘China B-share’ market was opened solely for foreign investors. The Hong Kong Stock Exchange was integrated into the Chinese system in 1997. Due to this exchange being previously under British control, it was more privatized than other exchanges. The ‘China H-shares’ market was created, representing the stock of mainland China companies, listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and denominated in Hong Kong dollars, open to foreign buyers. |

| 2000s | In 2000, China was granted permanent trade relations with the United States, which led to China being accepted as a member of the WTO in 2001. During the 2000s the multidecade trends toward market liberalization slowed or even reversed in many respects. The CCP, perhaps fearful of growing private power and of increasing inequalities across social classes, began interfering with commerce. The party inserted government contacts and influence into many private enterprises and implemented illiberal regulations such as price controls and subsidies. | During this time the largest companies by market capitalization largely operated in “old economy” sectors such as real estate, financials, energy, and industrials. |

| 2010s | In 2013 Chinese President Xi Jinping was elected President. President Xi rolled out the Belt and Road Initiative—a massive infrastructure project with aims to span from Asia to East Europe. This involves pipelines, highway, and railways, expanding China’s influence and global use of the currency. The number of “Free Trade Zones” was expanded domestically, to promote commerce, reduce restrictions, and lower import duties and taxes. China’s economy has become further liberalized in certain respects, through the expansion of Free Trade Zones, development of asset markets, and relaxation of domestic currency controls. China continues to exist as a model of state-controlled capitalism―a stark contrast to the West’s expectation that China’s integration into the global economy would inevitably lead to the adoption of democratic capitalism and ideals. | “New economy” businesses in technology, consumer cyclicals, and communication services begin leading major indexes during this time. The Chinese Communist Party continued to reassert influence into private enterprises, creating difficulty in truly knowing whether certain businesses should be classified as private or state-owned. |

The ‘China story’ & impacts of Chinese assets on portfolios

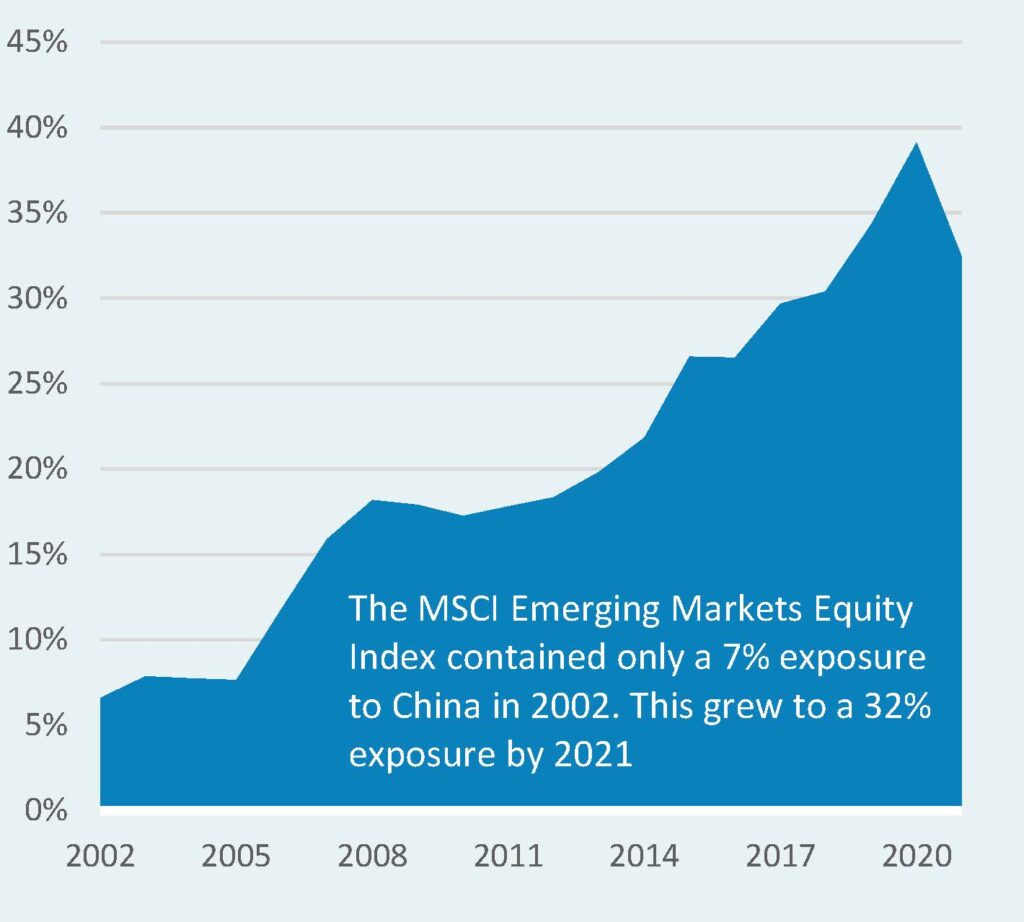

Most investors have likely allocated an increasingly larger portion of their portfolio to China by default, regardless of whether they have any sort of active or directional view on Chinese assets. This is due to two effects: a) the market capitalization of Chinese assets has grown over time which has naturally translated to a greater importance of China within common benchmarks, and b) most common benchmark providers have intentionally and significantly increased the weight of Chinese assets within their benchmarks as these markets have developed. In other words, the “neutral” exposure to Chinese assets in investors’ portfolios today is much, much larger than it has been in the past. In 2002, China made up only 7% of the overall emerging market equity index. By 2022 this had risen to nearly one third of the total index3. Taking a look at investors’ overall equity portfolios, China made up less than one half of one percent in 2002. This exposure had grown to 3.6% by 20224.

Investors may be well-served by acknowledging their quickly growing exposure to Chinese assets, and gauging whether this level of exposure is appropriate, or too much, or too little in relation to their personal views of Chinese equities and risks involved.

Figure 1: Importance of China in major indexes

|  |

The ‘China story’

In addition to the quickly growing size of China in major indices, some investors have opted to increase their China exposure above and beyond these benchmark weights, often through a dedicated standalone China equity mandate. Perhaps a contributor to such enthusiasm and therefore accelerating investments in China is the attractiveness and intuitiveness of what we might refer to as the ‘China story’. The China story, in admittedly very simplistic terms, is the common narrative that because China is a major powerhouse of global growth, and because China may very likely soon become the world’s largest economy, that investors will miss out on the big gains of Chinese markets if they do not make larger investments into these assets.

Although this thesis seems compelling, some investors may reasonably have questions. First, this thesis implies a fairly strong link between the economic growth of a country and that country’s ultimate asset market performance. Looking back through history, has a strong link existed between national GDP growth and the stock market performance of that country? Second, how has the China outperformance thesis worked out so far? Have Chinese markets in fact delivered extraordinary returns to investors throughout the last few decades as China’s economy grew in impressive fashion? Below we work to answer these two questions.

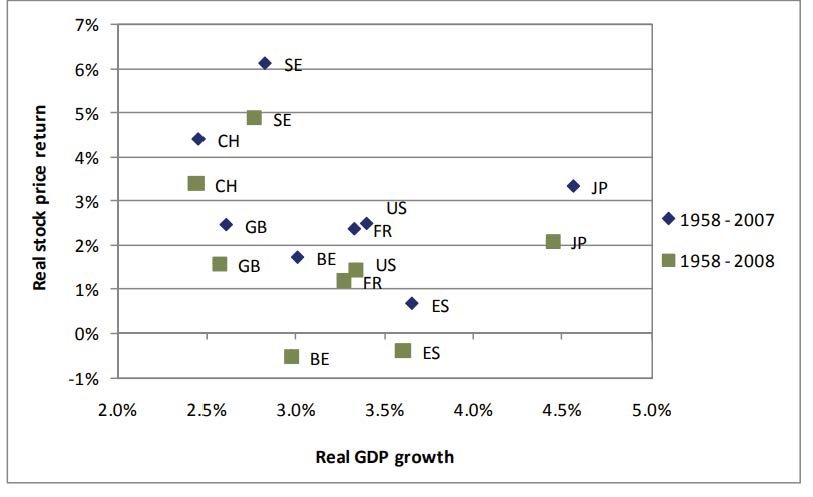

The idea that China is growing quickly to become perhaps the largest economy in the world, and that this warrants larger allocations to Chinese assets, implies a fairly strong link between the economic growth of China and the ultimate performance of Chinese stocks. A reasonable investor might look to history to gauge the past relationship between strength of economic growth and the performance of equity markets. There are many such studies available, and here we cite a 50-year study published by MSCI, titled Is There a Link Between GDP Growth and Equity Returns?5. The results are displayed below.

Figure 2: Relationship between economic growth & asset performance

Interestingly, this research suggests there is often little or no end-relationship between the strength of a country’s economic growth and that country’s stock market performance.

There exist a wide variety of reasons why stock market performance may not track closely with economic growth. A few of those reasons include:

- A country’s stock market most likely contains companies that conduct business internationally, leaving these companies more sensitive to international rather than domestic GDP growth.

- Most countries trade internationally, which means that their rate of economic growth is somewhat dependent on international trends and their trading partners’ economies.

- Investors often possess varying levels of access to companies and of course are not instantly grantedstock ownership upon the founding of each company within a market (foreign investors may be disadvantaged in their level of access to a local market, or companies might stay private longer which leads public equity investors to miss out on large gains, for example).

- Stock valuations change through time which can substantially influence long-term performance (the Japanese equity market boom and bust of the 1980s serves as a salient example of this effect).

Many of the variables above are particularly applicable to China, given its export focus, its high level of international trade, the restrictions placed on foreign investors, and the occasionally wild swings of its stock market. In short, a stronger local economy is of course positive for local equity markets, all else equal. However, a broad host of other variables and considerations exist that tend to muddy the overall picture, often resulting in a very weak end-relationship between GDP growth and relative stock market performance. As is often the case with markets, the situation is a bit more complex than we might hope.

Has Chinese economic outperformance led to market outperformance?

Next, we take a look at whether Chinese assets have in fact delivered on the ‘China story’. This story implies that the rise of China as a global power should have come hand-in-hand with spectacular equity market performance. Chinese equity performance is illustrated below. To avoid the starting point bias that often plagues this sort of analysis, we provide cumulative relative performance of Chinese markets using four distinct starting points6.

Figure 3: Cumulative China equity performance

|  |

|  |

Interestingly, Chinese markets have not necessarily delivered outperformance to investors over the long term, despite the dramatic success of China’s economy. China’s rise to a global economic superpower coincided with mixed Chinese equity market performance during most periods. Though, to be fair, it is worth noting that these conclusions may have been different if this paper were written in early 2021, prior to China’s sharp market correction.

As we illustrated in the commentary above, there are a variety of ways to access Chinese markets depending in the nationality of the investor, the currency in which assets are denominated, etc. The share classes mentioned in the first section of this paper are recapped below for convenience:

Interestingly, Chinese markets have not necessarily delivered outperformance to investors over the long term, despite the dramatic success of China’s economy. China’s rise to a global economic superpower coincided with mixed Chinese equity market performance during most periods. Though, to be fair, it is worth noting that these conclusions may have been different if this paper were written in early 2021, prior to China’s sharp market correction.

As we illustrated in the commentary above, there are a variety of ways to access Chinese markets depending in the nationality of the investor, the currency in which assets are denominated, etc. The share classes mentioned in the first section of this paper are recapped below for convenience:

- A-shares: stock of mainland Chinese companies listed on Chinese exchanges, accessible to only to Chinese investors, denominated in Renminbi

- B-shares: stock of mainland Chinese companies listed on Chinese exchanges, accessible to foreign investors, denominated in foreign currencies

- H-shares: stock of mainland China companies listed on the Hong Kong Exchange, open to both foreign and Chinese investors, denominated in Hong Kong dollars

We use the MSCI China Index throughout this white paper to represent performance as it widely referenced in the industry and represents a reasonable composition of Chinese stocks within a U.S.-domiciled investment portfolio. This index includes large- and mid-capitalization China A-shares, H-shares, and a variety of other foreign listings (ADRs). The index covers approximately 85% of the China equity universe, and also includes the impacts of currency market movements, which is appropriate as it is rare for U.S. investors to hedge the currency risk of their investments in Chinese markets. We provide the performance of this index since inception below, alongside the performance of A-shares, B-shares, and H-shares. As demonstrated here, an investor’s method of accessing Chinese markets has had a large impact on the performance outcome.

Figure 4: Historical China equity performance

Figure 5: Cumulative China index performance

Opportunities & threats

We have outlined our belief in this white paper that the ‘China story’, as often touted, is a bit too simplistic in its assumptions and may lack sufficient detail and nuance. In our view, the attractiveness of Chinese assets as a long-term investment should be evaluated similarly to all other asset classes in which an investor may allocate to. China equities are not an easy fat pitch investment idea just because of the size of China’s economy or its higher GDP growth rate7, and the historical lackluster performance of Chinese equities are testament to this.

In this section we identify opportunities and threats to Chinese markets, which we hope will assist investors in deciding their preferred level of exposure to this market.

Opportunities

- Valuations: during the first half of 2022 Chinese markets experienced a -49% fall from peak. This significant drawdown brought the MSCI China Index forward price/earnings ratio temporarily below 10x in April, ending the month at 10.4x. Valuations are materially cheaper than the broader MSCI Emerging Market Index forward price/earnings ratio of 11.5x, and substantially cheaper than the MSCI USA Index forward price/earnings ratio of 18.2x. In an environment of generally rich market prices, China seems to offer value.

- Peak COVID-19 pessimism: Much of China’s recent market volatility can arguably be attributed to the country’s extreme approach to COVID-19 and the reclosure of many major cities in 2022 as the Omicron variant spread. These sudden closures involved confining citizens to their residences and once again placing severe restrictions on various aspects of economic activity. Government policies have led to nationwide food shortages, a significant hampering of logistics at major Chinese ports, and fears of another recession. If markets have in fact overreacted to this news, given the mild nature of Omicron and the assumption that lockdowns will be temporary, this could present an attractive entry point for investment.

- The rising middle class and China’s inward transition toward consumption: During the 2010s Chinese leadership communicated its vision to transform the country from a manufacturing-heavy export-led economy to a richer middle-class consumption-led economy. This transition has proven difficult historically for many nations, but if navigated successfully could unlock a massive Chinese middle class consumer base and present a medium-to-long term economic opportunity for investors.

- Moderation of 2020 regulatory crackdown: During late 2020 the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) pursued a nationwide crackdown on a variety of industries, creating much uncertainty for businesses and slamming share prices. Evidence so far suggests that these crackdowns are easing and will perhaps soon be in the rearview mirror. If it turns out later that markets have punished assets too severely, a rebound in valuations and strong performance may follow.

Threats

- Instability of domestic real estate market: Much of China’s growth has been made possible by immense investment in infrastructure and real estate. Harvard Professor of Public Policy & Economics Kenneth Rogoff and IMF Economist Yuanchen Yang opined recently that the property sector in China makes up approximately 29% of China’s annual GDP. It is estimated that 70% of Chinese household wealth is tied up in real estate, which compares to 46% in the United States8. The price of an average property in Shanghai is nearly 50 times the annual earnings of an average city worker. To place this figure in perspective, Shanghai property prices are more than 5 times more expensive than New York City relative to local average incomes (New York City price-to-income is only 9.2)9. This high dependence on the real estate market creates concerns, given the Evergrande bond default in late 2021, and more recently Sunac China Holdings, which defaulted on a $740 million bond in early May. A more widespread real estate crisis could hit the economy very hard if development slows, and may be a core risk to future consumer spending since the net worth of so many Chinese depends on the equity in their homes.

- Slowing population growth: China’s population grew at a 0.03% rate in 2021, continuing a fairly steady downtrend in recent decades. If this trend continues, the country’s population will likely begin contracting within the next few years. An economy’s GDP is a direct product of the number of workers and the productivity of these workers, which means declining population would drag the economy lower, all else equal.

- Risk of Taiwan invasion: The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has ramped up rhetoric around Taiwan in recent years. President Xi Jinping claimed that “reunification” with Taiwan “must be fulfilled”. China has increasingly invaded the airspace of Taiwan, which has committed to defending itself against aggression from its larger and more powerful neighbor. Many geopolitical experts believe that China has been carefully monitoring Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to gather intelligence regarding how the West reacts, and could use this information to determine a strategy for invading Taiwan. If an investor were to assume that the unprecedented global sanctions on Russia might also resemble the West’s reaction to China in the case of a Taiwan invasion, this presents obvious tail risks for Chinese equites.

- China’s “Common Prosperity” initiative / Rule of Law: If instead of softening the regulatory stance, the CCP continues or ramps up their hardline approach to businesses, this could lead to greater pessimism and further discounting of Chinese assets. A growing wealth disparity, perception of unfairness in society, and also larger government interests in reducing the amount of power concentrated in private hands could give rise to this scenario. This ties to broader concerns among investors around the degree to which China can be said to have the Rule of Law. This concept, which involves the independence of the legal system and the certainty of fair and equal application of the law, is important for investors so they can have confidence in the security of their investment. Marked challenges to the rule of law could be red flags for investors with respect to their investment allocation to China.

- Growing global recognition of ESG concerns: Without intending to wade into a political discussion, we would be remiss if we did not briefly mention the expanding investor interest in ESG and the possibility that these efforts may soon turn to foreign nations such as China. As has been demonstrated recently in the case of fossil fuel divestment, for example, the turning of popular opinion can have very real impacts on businesses and entire sectors. If ESG investor focus were to turn to concerns in China around human rights abuses of the ethnic Uyghur people, or mass surveillance of the Chinese population, for example, a sea change in public sentiment could generate acute tail risk and headline risk for investors in Chinese assets.

Conclusion

China’s ascension over the past twenty years to the second largest economy in the world has changed the global landscape in a variety of ways. As China’s economic size and market capitalization grows, many investors have reasonably been pondering how to treat their allocations to Chinese assets. In this Topic of Interest white paper, we discussed the rise of China as an economic power and the development of Chinese asset markets. Second, we outlined the average investor’s exposure to Chinese assets over time and how this exposure has risen due the growing market capitalization of Chinese assets, and due to common benchmark providers significantly increasing the weight of China within benchmarks. We believe investors should be aware of the degree to which they are likely already more heavily invested in China via these benchmark considerations and may choose to evaluate whether they are comfortable with this sizable allocation to China, or would instead be more comfortable with greater or less exposure to this marketplace. Third, we took a deeper look at the ‘China story’ that has led many institutions to allocate more capital to this market, and identified the historical performance impact of Chinese assets on portfolios. In our view, the attractiveness of Chinese assets as a long-term investment should be evaluated similarly to all other asset classes in which an investment may allocate to. China equities are not necessarily an easy fat pitch investment idea just because of the size or strength of China’s economy, and the longer-term lackluster performance of these assets, despite the country’s spectacular economic rise, are perhaps testament to this belief. Last, we offered some opportunities and threats which Chinese markets present, providing context to investors in deciding the level of exposure to this market that is comfortable for their risk tolerance and investment objectives. As always, please reach out to your Verus consultant for additional details or discussion.

1 The Cultural Revolution was launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and involved wide-sweeping social and economic changes aimed at eliminating capitalist features of Chinese society in order to preserve communism. This was a period of intense internal uprising and conflict, leading to persecution and mass loss of life. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) eventually acknowledged that this period was unprecedented in the degree to which it set back the economy and the people of China. In current day this period is often referred to as “10 years of chaos”.

2 We use the term “reopened” here, as China’s first stock exchange opened its doors in 1860s but was closed in 1950 during the communist revolution and remained closed for 40 years. Prior to its closing in 1950, the Shanghai Stock Exchange was the largest exchange in Asia.

3 MSCI Emerging Markets Index, as of 12/31/21

4 MSCI All Country World Index, as of 12/31/21

5 MSCI Barra (2010). Is There a Link Between GDP Growth and Equity Returns? https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/a134c5d5-dca0-420d-875d-06adb948f578

6 Any time an investor creates or views a cumulative return chart it is important to acknowledge that the chosen starting point of that chart (the day/month/year which the data in the chart begins) can often skew the conclusions of the analysis.

7 Though at the time of this writing, China’s GDP growth rate had weakened materially and is more in line with that of developed nations.

8 United States Census Bureau, 2019

9 As referenced from Numbeo, the world’s largest cost of living database, crowdsourced from more than 7.8 million contributors globally. https://www.numbeo.com/property-investment/compare_cities.jsp?country1=China&city1=Shanghai&country2=Hong+Kong&city2=Hong+Kong