Download the Topic of Interest (PDF)

Many aspects of investing are fundamentally rooted in the idea that total investment return includes both investment income and investment price appreciation (growth). Nearly every asset class can be decomposed into these two characteristics—some assets being composed mostly of income and some assets being composed mostly of price appreciation. As interest rates have fallen around the world, the importance of income, and the role it plays in portfolios, has seen a dramatic increase. In this Topic of Interest, we revisit these two fundamental characteristics to provide investors with a lens with which to view decision-making in the current market environment.

Introduction

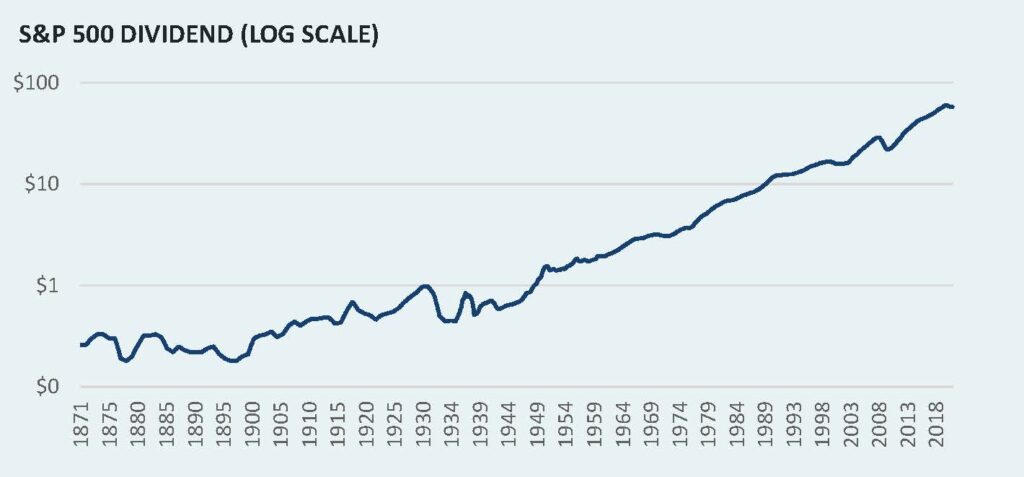

The income of an investment is defined as the return that the asset provides if the price of that asset does not change. This income is often backed by contractual obligations, such as coupons paid by a bond. Income that is not backed by contractual obligation may be backed by ongoing business operations that supply cash flows comfortably greater than required business expenses. In other words, income that is not contractually obligated may nonetheless be dependable and steady¹. An example is stock dividends, which corporations tend to maintain or increase gradually through time if at all possible. Certain stocks may be categorized as ‘dividend stocks’ if the business has a history of paying out generous and consistent dividends, providing steady income to investors. The securities of utility companies often fall into this category. Utilities tend to pay higher dividends, and the prices of these stocks have been relatively stable. Income investing overall tends to be attractive to investors who are less comfortable risking their investment principal, and who are willing to accept a lower rate of return for this safety.

However, it is important to note here that income is not dependable in all situations—a business that goes bankrupt cannot pay dividends, and a debtor in dire financial straits may halt interest payments despite the contractual obligation to do so. High yield bonds provide a frequent example of this dynamic. As an asset becomes riskier, the price of that asset will fall, all else equal. Because yield is defined as the income of an investment divided by the price of that asset, falling price due to risk results in a higher yield. Higher yielding debt, higher yielding equity, and other high yielding instruments are often awarded their ‘high yield’ status as a direct result of the greater perceived risk of the income attached to those assets².

On the other hand, investors hold certain assets with the expectation that most of their investment returns will be achieved through price appreciation. The price appreciation of an asset is the return that the asset provides due to its price increasing (price can of course also decrease, though that is rarely a goal), which is achieved through growth as the economic prospects for that asset improves (example: the continued success of a business results in a higher stock price), and/or a bull market (a rising tide lifts all boats)³. This type of return is not backed by any contractual obligation. Price appreciation is generally a more fleeting and uncertain source of return, relative to income. Public equities are a common example of an asset focused on price appreciation, as equity markets have delivered most of their returns through increases in price rather than through income. A more extreme example is venture capital, which involves investments in younger businesses that are focused on very fast-paced growth. This type of investing likely involves no dividends (no income) and is entirely dependent on price appreciation. Many of these underlying businesses might fail and result in investment losses, but a small number of businesses will (hopefully) experience dramatic growth that provides investors with a large return to compensate for the other losses. Investing for price appreciation tends to be attractive to investors who seek high returns and are willing to stomach greater volatility and the possibility of large losses in order to achieve those returns.

In this research paper, we discuss and quantify the importance of these two characteristics across major asset classes. Then, we demonstrate that these characteristics are at the root of many common issues that investors face. Last, we outline how these concepts tie into longer-term capital markets behavior, and how we think about income versus price appreciation in a low interest rate environment. It is worth noting that distilling investments into two components—‘income’ and ‘price appreciation’—can get a bit murky in certain asset classes and will inherently involve some simplifying assumptions. However, we believe this broad framework will serve investors well in their thinking around portfolio design and in asset allocation conversations more broadly.

Viewing asset classes through an income & price appreciation lens

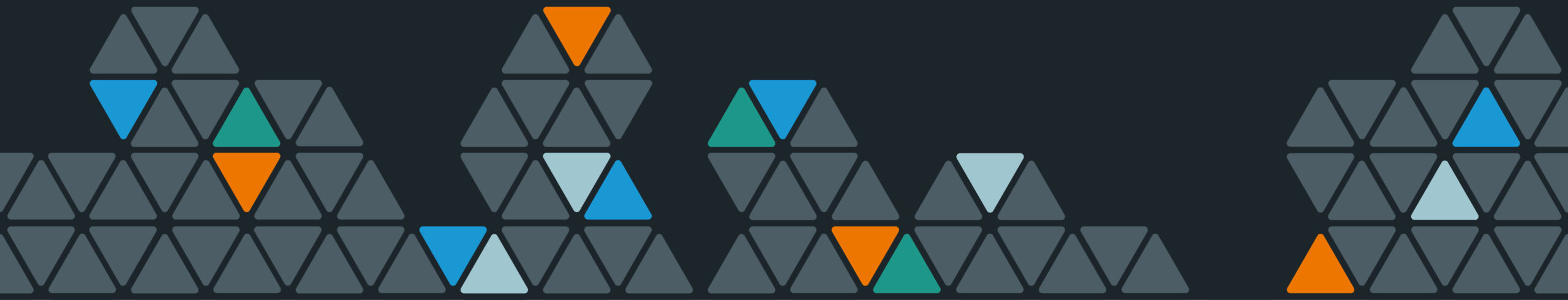

Using these concepts, we can remove labels from asset classes and instead think of behavior in terms of income and price appreciation. First, we take a look at U.S. equity. Investors receive income (dividends) from the equity market, and also (hopefully) benefit from price appreciation as corporations reinvest much of their earnings, growing businesses and raising the value of shares. The S&P 500 performance of income and price appreciation is displayed below. A key observation is that income has been fairly stable historically, while price appreciation has varied quite a bit.

U.S. Equity: Income vs. Price Appreciation

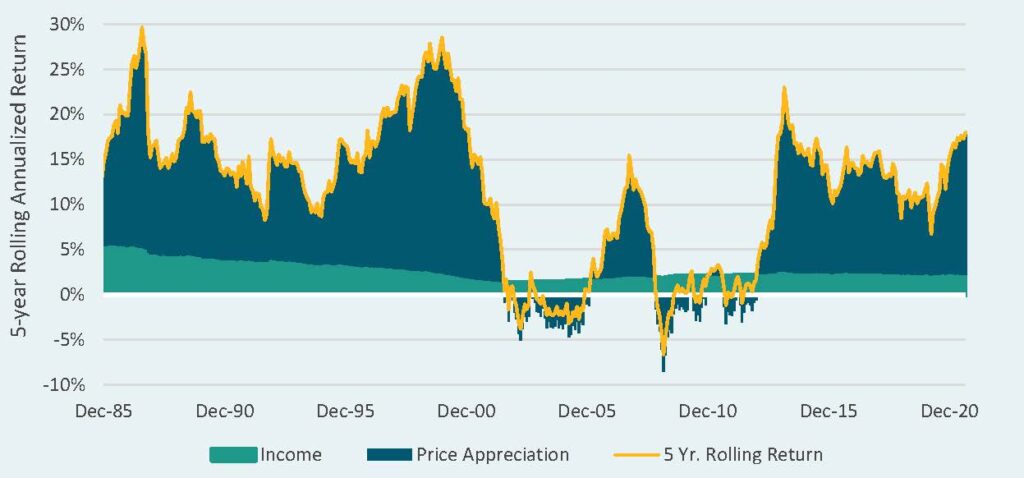

Next, we examine the 10-year rolling return decomposition of U.S. fixed income, using the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index as a proxy for the U.S. bond market. Here the income return represents the return investors receive from coupon payments, while price appreciation (or depreciation) represents the impact of fluctuations in the value of these bonds due to interest rate changes, changes in credit spread levels, etc. Unsurprisingly, bonds have delivered a very steady return relative to the returns experienced in the equity market, and as demonstrated here, this is likely related to the fact that nearly all of the return of bonds has been fueled by income (and income has been more dependable than price appreciation as a source of return). We can also observe that fixed income returns have been in secular decline since the early 1980s, as interest rates (i.e. income) have been falling since that time. Over longer time horizons, price appreciation has had a very small relative impact on an investor’s total return. This is a fundamental reason for which investors tend to think of bonds as a diversifier and ballast within portfolios.

Fixed income: Income vs. Price Appreciation4

As another example, we look at private real estate performance, separated into income (from properties), and price appreciation (the gain or loss from property value fluctuations). As demonstrated again, income has been fairly dependable while the return from price appreciation has been more volatile.

Core Real Estate: Income vs. Price Appreciation

Let us now shift focus to commodities. In a previous Topic of Interest paper5, we discussed that gains and losses from holding commodities futures contracts are more complicated than simply earning a return through changes in commodity price. Holding futures contracts is associated with three different types of return: changes in the price of the commodity (known as “spot return”), the change in value of the commodity futures contract as the contract approaches maturity (known as “roll yield”), and the interest income an investor realizes from the collateral they must post when entering a futures contract (known as “collateral yield”). Below we provide an analysis of commodities in terms of income and price appreciation components.

Similar to what has been illustrated for the other asset classes decomposed above, the income component of commodities returns was a much larger contributor to total returns in the 1970s and 1980s, but its impact has been in secular decline over the last 30 years as interest rates have approached zero in the United States. This means that the role of the income component of commodities total return has diminished materially in recent decades. Looking ahead, total returns in the space will likely be dominated by the impact of price appreciation (spot and roll return).

Commodities: Income vs. Price Appreciation

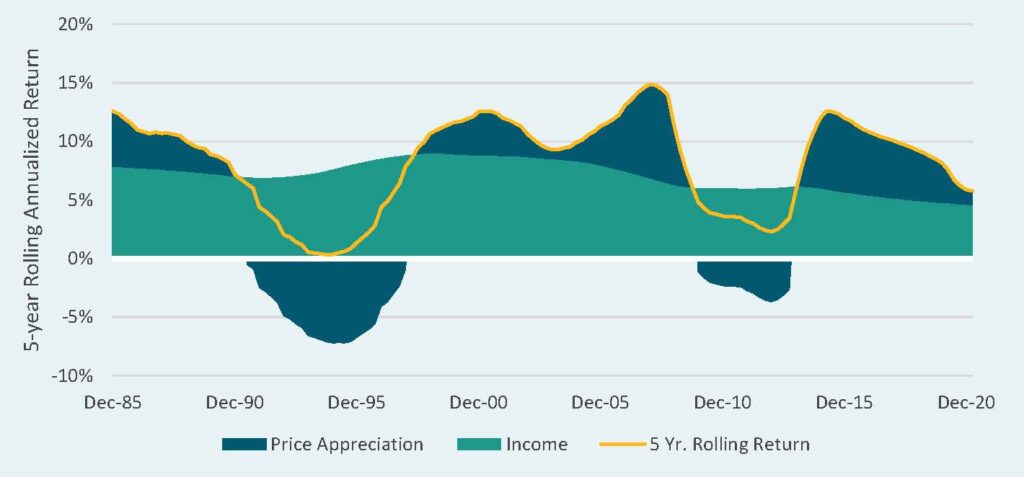

Each of these asset classes illustrate a theme that exists across most markets—that income tends to be more (often much more) stable and dependable than price appreciation. In the table below we provide an illustration of major asset classes and the extent to which income and price appreciation have contributed to the long-term returns of each asset class. Also below, we demonstrate the extent to which income and price appreciation have contributed to the returns of a simple 60/40 U.S. equity and fixed income portfolio over that time period.

20-year Return Decomposition: Income vs. Price Appreciation

These concepts are at the heart of many investment topics

Achieving a balance between income and price appreciation is central to many common topics that investors face. A more in-depth understanding of these dynamics across asset classes may add useful perspective to these conversations. Below are a few examples:

- Risk Tolerance: An investor’s risk tolerance often boils down to the decision of how much exposure to equities and how much exposure to fixed income is appropriate to hold in the portfolio, with a greater allocation to equities translating to higher volatility and increased uncertainty regarding future outcomes. Let’s imagine a market environment where safe fixed income (U.S. Treasuries) was yielding 7%. If an investor’s return target was also 7%, the need to invest in equities would be drastically diminished, because safe bonds would offer enough yield to meet the investor’s needs. In this somewhat ideal environment, the investor could achieve most (or all) of their investment return by depending on income. This would be an environment that should excite most investors. But even more exciting is the fact that the yield of fixed income at any point in time has been a fairly strong predictor of future performance of fixed income. In other words, an environment of high interest rates is likely one that would allow investors to achieve their portfolio objectives through income—a more stable and dependable return source—effectively removing much of the volatility and uncertainty from the portfolio management process.

- Value vs Growth: ‘Value investing’ relates to the idea of identifying undervalued assets that are attractively priced. In many situations, a ‘value’ investment may pay off handsomely even if the price does not move after investment. This is because very low price often means a higher yield, and therefore high return from yield (meaning price appreciation is less important). In contrast, ‘growth investing’ involves identifying assets that may grow at an impressive pace, therefore delivering strong performance from price appreciation. In terms of income and price appreciation, we might say that value investing and growth investing are opposites.

- Retirement Planning: Retirement planning typically revolves around the idea of younger aged investors placing more focus on growth assets, and then gradually shifting their portfolio toward stable income-producing assets later in life. At retirement, an investor will ideally hold most of their portfolio in income-producing assets (i.e. bonds) and less of the portfolio in growth assets such as equities. Once again, this ties to the fundamental idea that ‘price appreciation’ is a riskier source of return than ‘income’. In retirement, stable and dependable incomeis an attractive quality, while the more volatile and fleeting nature of price appreciation may be less attractive. Hypothetically, if a retiree receives 100% of their ongoing living expenses through income-producing assets, that retiree may care very little about shorter-term fluctuations in the value of their investment account, as long as the income produced by the account remains stable. This is a much different situation from an investor who invests for growth, since movement in price is the primary source of return for growth investing.

Taking a longer-term perspective

The dynamics of income and price appreciation have shifted considerably in recent decades, as interest rates have declined to nearly zero. Unfortunately, investors now face an environment where income is perhaps scarcer than any time in history. As readers may have observed in the preceding analysis, income has historically been a key driver of returns in many major asset classes, and the return from income has been falling consistently for decades. These dynamics suggest that: 1) overall portfolio returns will likely be lower in the future, 2) investors may need to place greater focus on price appreciation in order to reach their investment objectives, and 3) a greater emphasis on price appreciation may come hand-in-hand with increased portfolio risk and uncertainty due to the less dependable nature of price appreciation as a source or return.

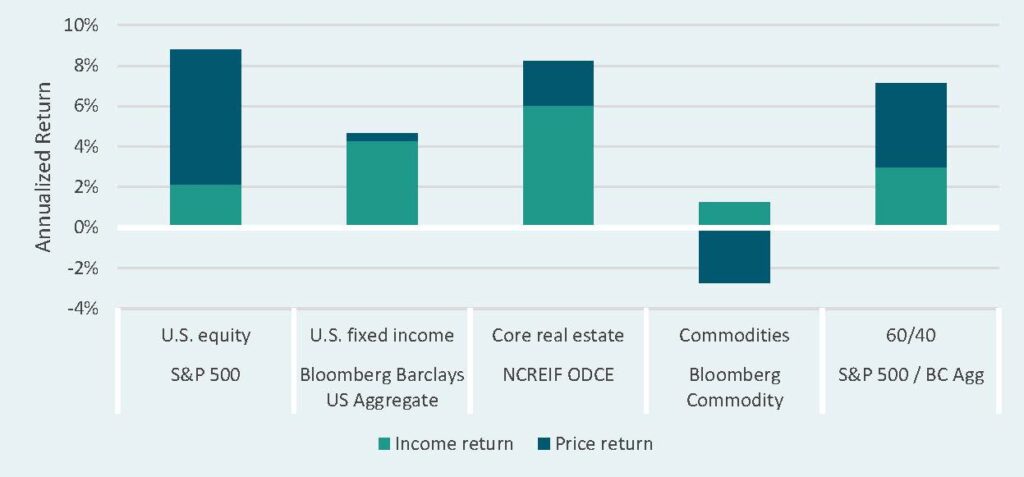

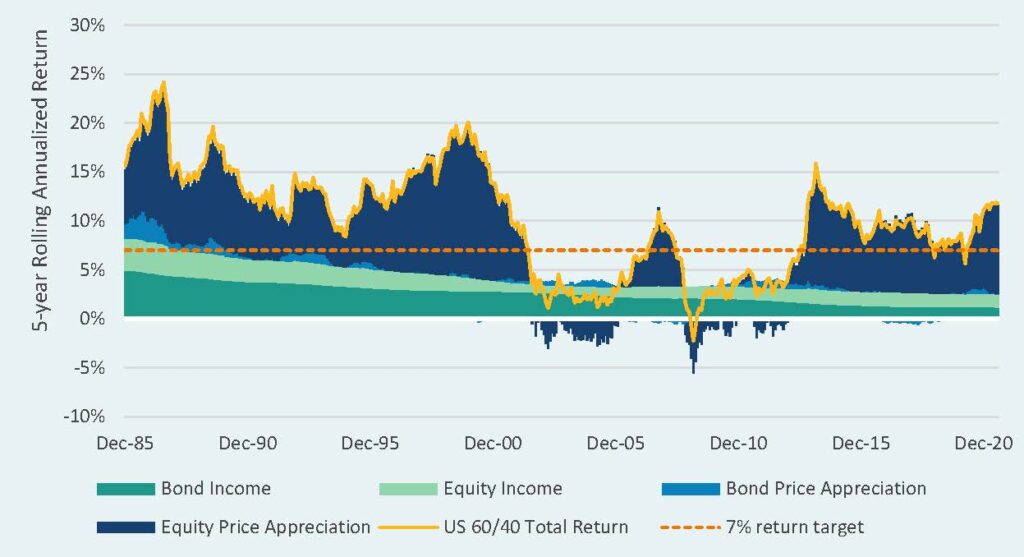

First, overall portfolio returns will likely be lower in the future. What supports this claim? We say this because income has historically been a major driver of asset returns. Losing income means that many assets are losing a return source. As a way to quantify this relationship, below is a chart that illustrates the extent to which income and price appreciation contributed to portfolio returns during recent decades, assuming a simple 60/40 portfolio with U.S. equity and core fixed income.

U.S. 60/40 Portfolio: Income vs. Price Appreciation

This chart illustrates the magnitude by which income has fallen, and the widening gap between income and a 7% return target, which price appreciation presumably needs to supplement. For example, in the 1980s an investor with a U.S. 60/40 portfolio would likely have achieved their 7% return target from income alone (bond coupons and equity dividends) over most five year periods. If we compare this to the most recent five-year trailing annualized period, however, an investor with the same simple portfolio would have required price appreciation to the tune of 4.5% in order to reach that same 7% return—a much higher hurdle. And it is important to note that there is no economic reason to believe that asset classes should produce greater price appreciation in a low-income environment. Furthermore, this problem is arguably compounded today due to two characteristics of the environment: a) interest rates are low and not far from 0% (which limits further bond price appreciation), and b) equity valuations are near record high levels (which limits further equity price appreciation). It is reasonable to expect that price appreciation in portfolios may be lower in the future than in the past, and also that there may actually be a greater risk of price depreciation in these asset classes. This is due to the fact that interest rates have more room to rise than to fall, and equity valuations have more room to fall than to rise, historically speaking.

Second, investors may need to place greater focus on price appreciation in order to reach their investment objectives. This should be apparent, as the loss of income may naturally push investors to make up for that loss by focusing more on assets with potential for price appreciation. What does this look like in practice? One obvious answer is heavier allocations to riskier assets. Private assets, for example, have seen a spectacular rush of popularity. The concentration of many private assets, potential for alpha, and leverage often allows for higher returns (along with, of course, higher risk). Another recent example involves the thoughtful use of leverage. Investors have used leverage to gain synthetic exposure (derivatives-based exposure) to fixed income, instead of traditional cash investment. This frees up cash in the portfolio to be dedicated towards higher-returning investments (i.e. assets focused on price appreciation)6. In other words, because bonds are contributing far less to investor’s return targets, some investors are instead gaining exposure to bonds through derivatives in order to free up space in the portfolio (free up cash) to refocus that cash on assets that will hopefully make a greater contribution to return objectives.

Third, a greater emphasis on price appreciation may come hand-in-hand with increased portfolio risk and uncertainty due to the less dependable nature of price appreciation as a source of return. We hope the data and explanations in this white paper help hit home on this point. As displayed across the asset class histories on the preceding pages, income tends to be a dependable source of return, while price appreciation tends to be fleeting and can deliver losses (often large ones) to investors for extended periods of time. Today, income has less to offer, which means that investors must face decisions such as: retaining existing portfolio structures and simply adjusting future return assumptions downward, partially divesting from income-producing assets and reallocating to assets that may provide more price appreciation, and/or identifying creative strategies involving leverage to improve portfolio efficiency.

Concluding thoughts

Many aspects of investing are fundamentally rooted in the idea that total investment return includes both investment income and investment price appreciation. Nearly every asset class can be decomposed into these two characteristics—some assets being composed mostly of income and some assets being composed mostly of price appreciation. Income and price appreciation are at the heart of many investment topics. In this research paper, we discussed and quantified the importance of these two characteristics across major asset classes. Then, we demonstrated that these characteristics are at the root of many common issues that investors face. Last, we outlined how these concepts tie into longer-term capital markets behavior, and how we think about income versus price appreciation in a low interest environment. For more information regarding our views on these topics, please reach out to your Verus consultant.

1 As demonstrated below, corporate dividend payouts have been extremely stable, despite there being no contractual obligation to make these payments to investors. Over the past century, dividends have been maintained despite recession in most instances.

2 Yield = Income divided by Price, which means that if Price falls due to an increasing risk that the issuer becomes faces financial difficulty or bankruptcy, this reduces the chance of repayment to the investor and the Yield of the investment increases. For this reason, safer assets tend to offer the lowest yields.

3 For illustrative purposes only. This is admittedly an overly simplistic and non-exhaustive explanation of why asset prices might appreciate.

4 Price return includes “Other Return”, calculated by Barclays. “Other Return” includes prepayment or writedown returns affecting primarily the securitized portion of the index.

5 https://www.verusinvestments.com/commodities-in-a-low-inflation-environment/

6 Fixed income remains an important part of portfolios, primarily for diversification purposes. Gaining exposure to fixed income via derivatives allows an investor to maintain that diversification while avoiding the opportunity costs of a cash investment in those bonds.